Rubin’s “No-Chiller” Shock: Who Loses, Who Wins, and Capex Shift

At CES 2026, NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang used the keynote stage to frame a new thermal-management claim around the upcoming Vera Rubin platform: Rubin-class systems can be cooled with 45°C (113°F) water, and therefore “no water chillers are necessary” for data centers in that design point.

That single sentence is why you saw an immediate “narrative shock” in HVAC-linked equities:

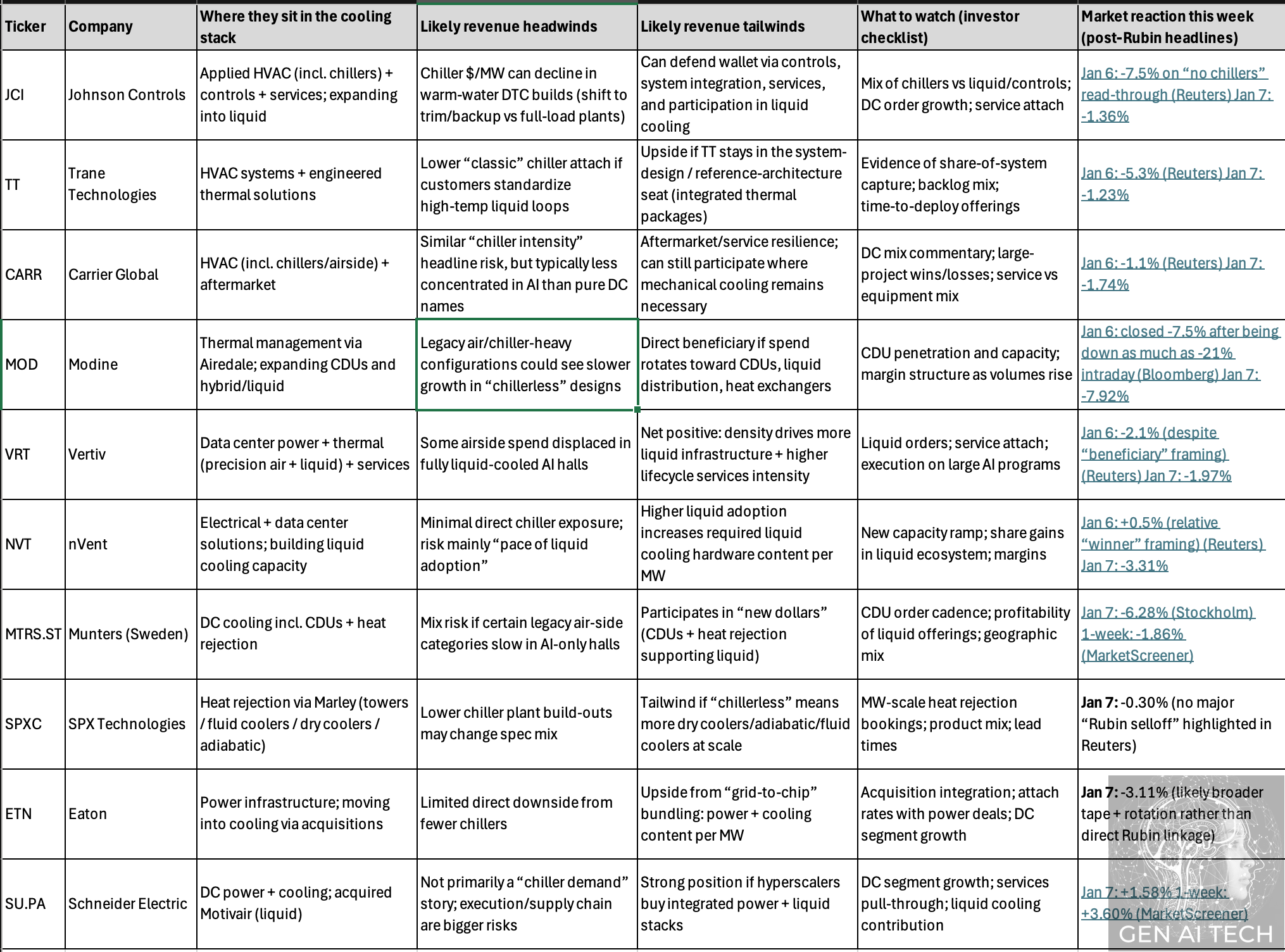

Johnson Controls (JCI) -7.5% and Trane Technologies (TT) -5.3% on January 6, 2026, both hitting multi‑month lows, per Reuters.

Barclays’ Julian Mitchell explicitly warned investors not to dismiss NVIDIA commentary as hype—even if it “seem[s] rather dramatic at first glance”—because of NVIDIA’s primacy in the AI ecosystem.

Barclays also quantified “AI data center exposure” (as a percent of sales) in a way that matters for public-market positioning: low‑double‑digits for JCI and ~10% for TT (Carrier cited at ~5%).

So the market’s instantaneous interpretation was: “No chillers” = demand impairment for chiller OEMs.

The more investable reality is subtler:

NVIDIA is not saying “cooling goes away.” It is saying the thermodynamic set point moves upward (hotter water), which can reduce compressor-based mechanical chilling in many deployments.

That shift reallocates cooling spend toward liquid distribution (CDUs, manifolds, piping), controls, and heat rejection (dry coolers / fluid coolers / towers), rather than eliminating it.

In other words: this is a mix shift story, not a “cooling capex collapses” story—and mix is exactly where winners/losers inside the thermal value chain get re-rated.

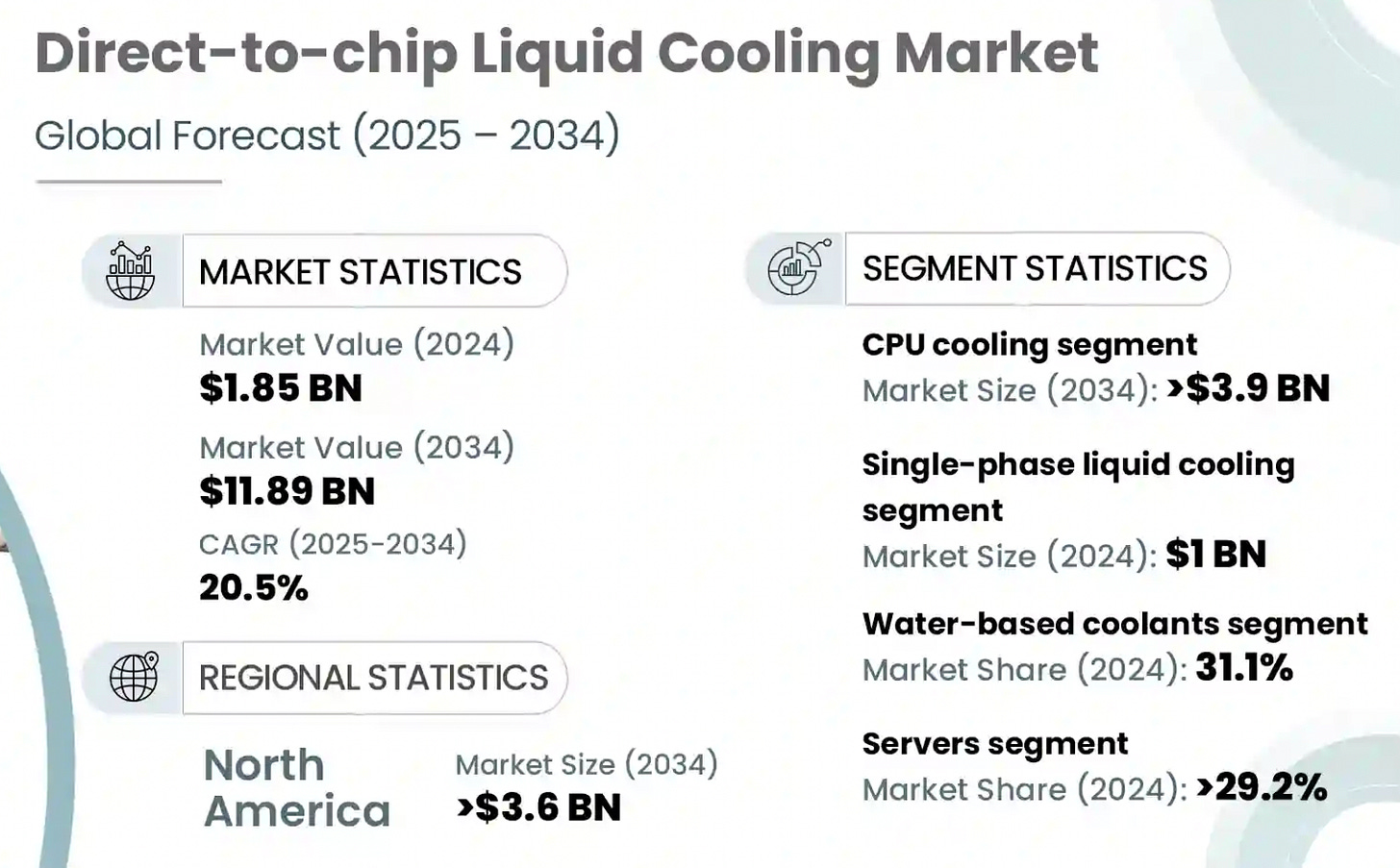

The response from our clients was immediate. Almost as soon as the data became public, we began fielding a surge of inquiries specifically focused on Direct-to-Chip (DTC) technology. Clients are no longer just asking about the general concept; they are aggressively scrutinizing the delta between historical adoption rates and the explosive growth projected for the next decade.

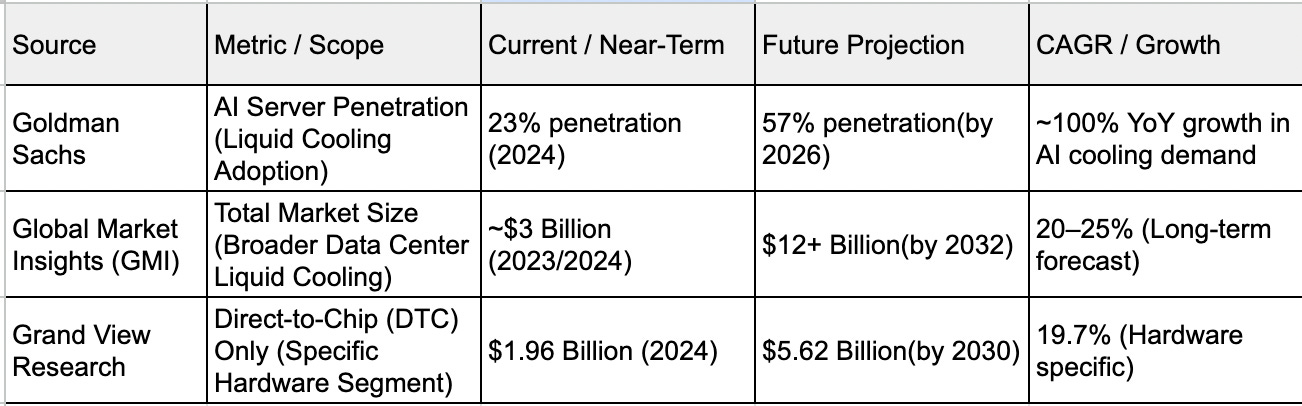

Let’s look at what has been projected so far:

Per McKinsey, $15-$20 billion in liquid cooling by 2030.

According to Goldman Sachs, the penetration of liquid cooling in AI servers is projected to more than double in just two years, jumping from 23% in 2024 to 57% by 2026.

This rapid standardization is reshaping the financial landscape of data center infrastructure: Global Market Insights forecasts the broader liquid cooling market will quadruple from roughly $3 billion today to over $12 billion by 2032.

Source: GMI Research

However, we believe even these aggressive projections are understated. The actual impact could be significantly larger as rack densities scale faster than anticipated, effectively forcing Direct Liquid Cooling (DLC) to graduate from a niche solution to the de facto utility for the AI era ahead of schedule.

In this article, we will dive into specific client questions:

Who loses revenue and who gains if Rubin reduces the need for chillers?

What does that imply for companies such as Johnson Controls (JCI), Trane (TT), Modine (MOD), Vertiv (VRT), and nVent (NVT)—and is the impact a lasting change in end demand or mostly a short-term market reaction?

Does “no chiller” actually mean “no chiller purchases”?

Stack level comparison between with Traditional DC (air-cooled / low density) “Rubin future” (liquid / “no chiller”) with “SKU / line-item” detail

Where does the cooling CAPEX go as racks get denser and liquid becomes standard?

1 MW “Cooling CaPex Mix” Model - four buckets - On a per-megawatt basis, how does spending reallocate away from chillers and air-side equipment (CRAH/CRAC) and toward CDUs, liquid distribution (manifolds/quick-connects/piping), and heat-rejection hardware (e.g., dry coolers or hybrid systems)?

How fast does warm-water direct-to-chip become the default in hyperscale AI builds?

Review Uptime’s 2025 Cooling Systems Survey

From 2026 to 2029, what is a realistic pace of adoption—and what slows it down in the real world (equipment availability, commissioning complexity, codes/permitting, water strategy, operational reliability concerns, and service readiness)?

Please note: The insights presented in this article are derived from confidential consultations our team has conducted with clients across private equity, hedge funds, startups, and investment banks, facilitated through specialized expert networks. Due to our agreements with these networks, we cannot reveal specific names from these discussions. Therefore, we offer a summarized version of these insights, ensuring valuable content while upholding our confidentiality commitments.

Q1. Who loses revenue and who gains if Rubin reduces the need for chillers?

Nvidia’s Rubin has a chassis devoid of visible cables, hoses, and fans has sent shockwaves through the infrastructure market, signaling a radical departure from traditional server design

Source: NVIDIA Blackwell Ultra GB300 vs. Vera Rubin compute tray

If NVIDIA’s Rubin‑era platforms truly enable higher‑temperature, direct‑to‑chip liquid cooling, our clients are asking a blunt question: which cooling vendors lose, and which win? The answer is not binary. Rubin does not remove the need for cooling; it reorders where cooling dollars are spent per megawatt. Mechanical refrigeration becomes less central, while liquid distribution, heat rejection, and system‑level integration grow in importance.

Here is an expansion on the specific tickers your clients are asking about, structured to clarify why they are moving and whether the market’s reaction is a signal or noise. Investors are currently scrambling to re-rate these companies based on who owns the “new” loop (CDUs/Manifolds) versus who owns the “old” loop (Chillers/CRAHs).

Revenue headwinds / tailwinds by ticker + “this week” market reaction Table